Atlantic Bluefin Tuna: A Stateless Fish!

When most people think about tuna, they think about sushi and sashimi, which is what tuna is appreciated for around the world. But do you really know what kind of fish a tuna is in the ocean?

Tuna is not just one species but a family that comprises 15 species, that belong to the tribe Thunnini , a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family.

Let’s take a closer look at one species in particular, the Atlantic bluefin tuna ( Thunnus thynnus) .

A bluefin tuna is what we call a top predator, which sits right at the top of the food chain. Mostly they eat what we call swarm fish – quite often herring, anchovy, sardines – anything that moves in large groups. But what is truly spectacular about this specimen is its capacity to cross the ocean many times to spawn in warm waters and back again to feed in cold waters. Indeed, Atlantic bluefins are pelagic predators and highly-migratory fish of a large size. They are also warm-blooded, a rare trait among fish.

They are equally at home in the cold waters of the North Atlantic, North Sea and Norwegian Sea as they are in the tropical waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean Sea. Their feeding grounds are generally in cold temperate waters and their spawning grounds in rather warm waters, allowing them to make a full-speed annual migration across the Atlantic Ocean.

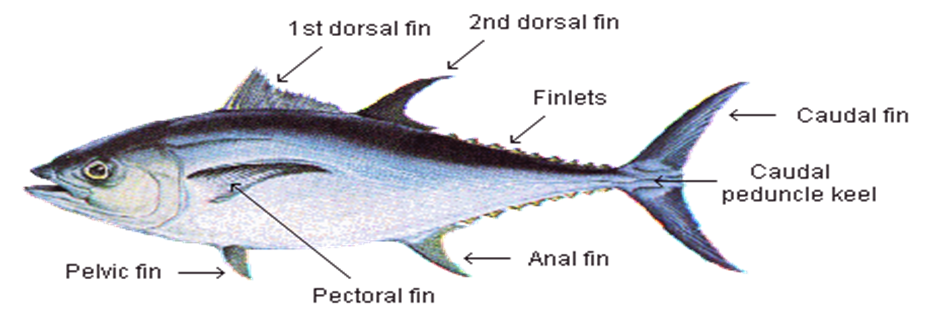

The Atlantic bluefin tuna is one of the largest, fastest, and most colourful fish in the world. Its streamlined torpedo-shaped body is designed for speed and endurance. Its colouring - metallic blue on top and shimmering silvery white on the underside - helps to camouflage it from above and below. Their voracious appetite and varied diet mean that they grow to a whopping average size of 1.5 metres long and 250 kilograms, although much larger specimens are not uncommon.

Bluefin tuna are also characterised by a slow growth, with age-at-maturity between 4 to 8 years, which depends a lot on the area they live in (for instance, east or west Atlantic populations). Their average natural lifespan is 15-30 years. (ICCAT, 2002).

Unfortunately for the species however, bluefin meat also happens to be regarded as surpassingly delicious, particularly among sashimi eaters, and overfishing throughout their range has driven their numbers to critically low levels. Historically, fishing bluefin tuna has a very long tradition in the Mediterranean Sea. Fishermen traditionally used hand lines and beach seine to catch bluefin tuna during their spawning migrations into the Mediterranean (J.M Fromentin; C. Ravier, 2014)

It has recently become highly profitable with the rapid emergence of the sushi-sashimi markets first in Japan and then in North America and Europe. Its highly-migratory behaviour makes it difficult to protect as bluefin tuna travel long distance at a fast pace across the Atlantic and therefore swim across multiple jurisdictions which require regulations for a stateless fish (T. C. Bestor, 2000)

References:

ICCAT. 2002. ICCAT workshop on bluefin tuna mixing. ICCAT. Coll. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT 54: 261–352.

J.M Fromentin, C. Ravier; Bulletin of Marine Science, 2005: The East Atlantic and Mediterranean bluefin tuna stock: Looking for sustainability in a context of large uncertainties and strong political pressures

T.C. Bestor; Foreign Policy, 2000: How sushi went global

SHARE THIS ARTICLE