Irish Cephalopods – From Mysterious Giants of the Deep to Species so Small they can Fit in Your Hand.

Fishing operations worked on smaller scales in 1875. Instead of the traditional fishing boats we think of today, fishermen worked aboard small corraghs’. The small narrow rowing boats often navigated off the west-coast of Ireland in search for their daily catch and they hauled in their bounty using line nets. It just so happened that on the 25th of April that year, fishermen sailing near Inishbofin, off Connemara, caught more than they were asking for on their line.

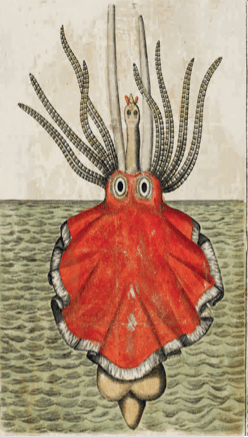

Figure 1: Illustration of “monster” washed ashore in Dingle Bay, 1672 (Wikipedia).

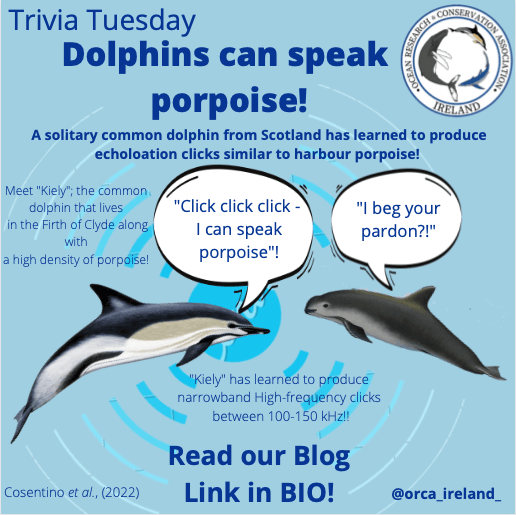

Basking on the surface of the water was a creature which instilled fear in fishermen and sailors alike - the kraken. A fearsome and elusive monster, capable of taking down sperm whales, drowning humans and even destroying boats. These days, we just call it just the giant squid ( Architeuthis dux) and acknowledge that its tremendous size is due to deep-sea gigantism.

Still, despite it not being a legendary monster capable of destruction, it was known that catching a giant squid was no easy feat. Once they had you in their tentacles, they could cut and bore into you. But on the 25th of April 1875, the fishermen could not bear to let such a good species be lost. A lengthy chase and battle lead to them severing the head and arms to bring to shore. These prized remains were preserved by Sergeant O’Connor and can still be found today in the Natural History Museum, in Trinity College Dublin.

This was the second ever record of the giant squid in Irish waters. The first record dates back to 1673. Letters serving as testimonials tell of a monster being washed ashore in Dingle Bay after a storm (see Fig.1).

Overall there have been less than 6 sightings of the Atlantic giant squid in Irish waters in the last 350 years with the latest being in 2017. Many of these sightings have been on the west-coast, around Kerry and off of Porcupine bank, an area near the continental shelf. Giant squids are deep diving species, being found at depths of 300-1000m, feeding on deep-sea fish or even cannibalising themselves. The myth of giant squid chasing and hunting sperm whales was twisted, as instead sperm whales are known to dive to great depths to prey on giant squid.

Figure 2. This much-reproduced photograph shows a giant squid found at Ranheim in Trondheimsfjord , Norway on 2 October 1954 , being examined by Professors Erling Sivertsen and Svein Haftorn. The unusually complete specimen measured 9.24 m in total length and had a mantle length of 1.79 m. Specimens such as this, if properly preserved, can provide important scientific data long after they are collected; the animal pictured had its beak morphometrics and tentacle morphology studied by Roeleveld (2000) and Roeleveld (2002) , respectively.

The fact they live at great depths explains why we’ve encountered the species so little. They only tend to surface or travel further up the water column when injured or sick. In fact, they are one of the few species of extant megafauna that is rarely photographed alive. The elusive species was photographed stranded in 2002, and in 2004 the first photos of the squid in its natural habitat were captured. It wasn’t until 2012 that the first footage of a live adult was filmed in Chichijima, Japan, and since then the giant squid has only been filmed two more times. On June 19, 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association recorded footage in the Gulf of Mexico of a juvenile giant squid at a depth of approximately 750m.

Figure 3. Atlantic giant squid preserved in ice.

Atlantic giant squids may be an impressive and rare find, but they aren’t the only exciting cephalopod species found in Irish waters. While the giant squid ranges between 10 to 13 metres, one of my favourite Irish cephalopod species is only 49 centimetres long in total. The common or European cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis ), can be found in warmer southern waters of Ireland. The fish in cuttlefish is null and void. Cuttlefish, like the giant squid, are cephalopods and belong in Phylum Mollusca.

Figure 5. European cuttlefish (Sepia officinals)

The cuttle in cuttlefish refers to their internal shell, called the cuttlebone (Fig. 6). Each species of cuttlefish all have distinctly different cuttlebone. The cuttlebone is a specialised oval of calcium carbonate which is filled with chambers which help control the cuttlefish’s buoyancy in water. The species can regulate this by allowing gas to empty or fill within the chambers. Often, this can be found washed up on beaches. Despite the English name being pretty self-explanatory, the species were referred to As Gaeilge as An Láir bhán (the white mare) for unknown reasons.

Figure 6: Calcium carbonate cuttlebone.

The mantle, which is the sack shaped part of the body, covers the cuttlebone and internal organs. It has long fins that cover each side of the mantle which undulate to help the cuttlefish move slowly within the water column. When there is a need for escape or attack however, cuttlefish are able to propel jets of water from their mantle cavities allowing them to move at fast speeds.

Not only can the mantle assist in jet propulsion but can likewise help make the cuttlefish seem larger as a form of defence mechanism. At the base of the mantle the head of the cuttlefish can be found. Cuttlefish have highly developed eyes which have large unusual shaped pupils, which look like the letter “W”. (Fig. 7).

Cuttlefish species cannot see colour, but instead see can interpret the polarization of light. This helps with their perception of contrast. It is hypothesised that cuttlefish eyes are fully developed before they are in born, and that in fact they start observing their surroundings while still in the egg! Despite not being able to see colour, cuttlefish are able to change colour when mating. Males have been found to use aggressive patterns to scare off other potential suiters, while using calmer colours to soothe and attract females.

The head contains beak like jaws, with eight sucker-bearing arms and two tentacles. The tentacles have two denticulated suckers which can also be retracted into the body, only to be shot out at high speeds to catch the cuttlefish’s prey. To small species, this is probably as terrifying as encountering a giant squid on your line.

Turns out you don’t have to travel far to experience incredibly diverse and intelligent life. Irish waters are home to many fascinating and ecologically important species all which are threatened by anthropogenic pressure. So maybe next time your local beach, have a think about all the wonderful Irish fauna there are present and how you yourself can help conserve and protect them.

If you see any cephalopods in Irish waters or stranded on beaches – become a citizen scientist! Send in any observations along with photographs to the Observers App - available for Android on Google Playor through our website www.orcireland.ie to help us map Irish marine life!

References:

Moore, A.. (1875). XVII. - Gigantic squid on the West Coast of Ireland. Annals and Magazine of Natural History . 16 (92). p.pp. 123–124.

Images:

All other non-Wikipedia images: Creative Commons on Microsoft Word.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE