Sea Turtles Create Decoy Nests to Limit Predation.

Every single turtle that survives to maturity is a real-life miracle - a 1 in 1000. 99.9% of the eggs laid on a nesting beach every year will not survive long enough to reproduce and contribute to the next generation. The reasons behind this include predators such as crabs and gulls that kill up to 50% of the turtles that emerge from the nest before they have even reached the ocean, as well as anthropogenic threats such as plastic, climate change and by-catch that are making the life of sea turtles even harder. These animals face threats before they even leave the protection of the egg.

During the nesting season, a female turtle will lay multiple clutches of eggs, returning to the ocean in between each nesting event. Each time, she will emerge from the ocean and move up high onto a sandy beach, probably close to where she first began her own life. Sea turtles generally lay around 50-130 eggs at a time. While they do not take care of their young, sea turtles create a nest cavity in sandy beaches for the eggs to develop until they hatch.

After laying their eggs, sea turtles refill the egg chamber, scatter sand around the nest site, and then return to the ocean. Once back in the water there is no parental care from the mother and the eggs are left to fend for themselves.

Since nest predation rates can be as high as 50% on some beaches, scientists previously presumed that sea turtles scatter sand in order to camouflage their nest. Animals such as gulls wait until the turtles emerge from their nest to begin predating on them, but there are predators that are able to dig up nests and actually prefer feeding on the eggs of turtles, including dingoes, foxes, and mongooses. Alternatively, some researchers consider the primary function of sand-scattering is to modify the nearby beach environment in order to optimize temperature and moisture conditions for egg development.

However, a recent study on the activity and movements of sea turtles has showed that sand-scattering is not primarily for disguising the nest nor for optimizing incubation conditions. Instead, it appears that sea turtles are creating decoy nests nearby in hopes to make it more difficult for egg-seeking predators and parasites to locate the eggs.

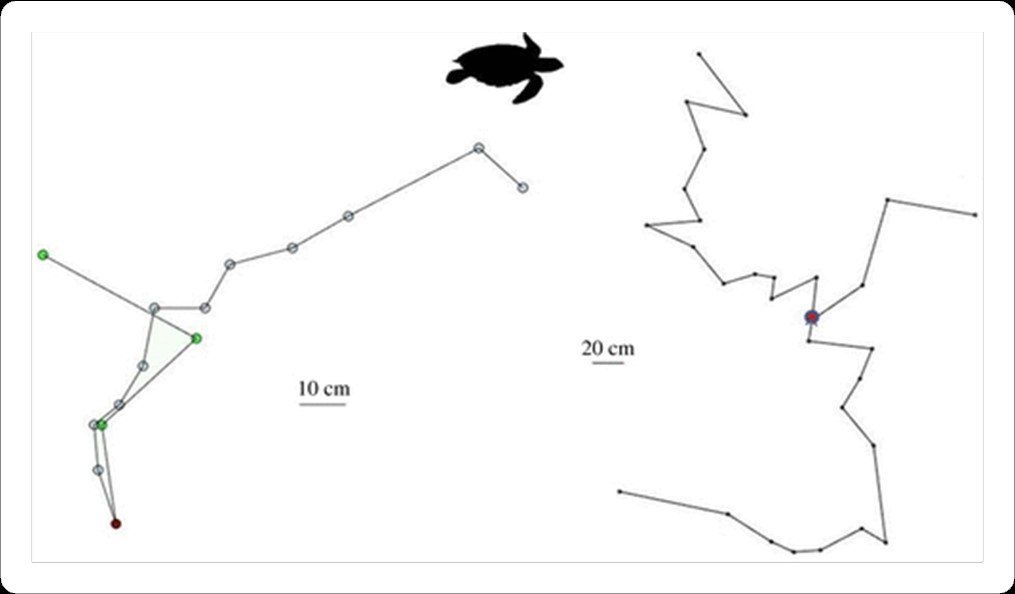

The movement of hawksbill ( Eretmochelys imbricata ) and leatherback ( Dermochelys coriacea ) turtles were monitored during this behaviour on a beach in Tobago. Findings showed that neither species stayed close to the nest, instead the turtles moved away, stopping at stations to sand-scatter using their flippers. They then changed direction and created a convoluted path back to the ocean. They repeated the process multiple times. It is now thought that the purpose of this behaviour is to create decoy nests to confuse predators, as well as to destroy evidence of disturbed sand texture or topography around the original nest. These decoy nests would increase the effort needed for predators such as mongooses to find and predate on the eggs, which has been shown to reduce predation risk.

But how did we come across these findings?

To track the turtle’s movements, scientists placed markers into the sand above the nest as well as on the tip of the turtle’s carapace. Then, they drew out field sketches noting the position of the markers and the path the turtles took. Once the turtles returned to sea, the distances and angles of turn were measured. The number of stations ranged from 1 to 24 and the distance between stations varied between 6 to 318cm, depending on the species.

The maps generated from this study showed that the route varied every time, as well as the number and position of decoy nests. Hawksbill turtles created on average seven decoy nests, whereas leatherbacks created closer to eleven; however, the number of scattering areas ranged dramatically. The distances between scattering areas ranged from 32 cm on average for hawksbills and 103 cm for leatherbacks, though these measurements also varied quite drastically. Additionally, changes in direction between sand-scattering areas ranged remarkably among individuals. The unpredictability of the position of these decoy nests is perhaps a way to prevent predators from working out a pattern in the disturbed sand.

Because sand-scattering appears highly variable, seemingly unpredictable, and progressively displaced from the real nest site, it appears that a more likely primary function for this behaviour would instead be described as a ‘decoy’ behaviour, as oppose to the previously thought ‘camouflaging’ or ‘incubation optimizing’ stage.

By creating decoy nests, sea turtles disturb sand topography, texture, and olfactory cues, preventing predators from discerning a pattern of disturbance in the sand and smelling out turtle scents. By doing this, turtles increase the search and excavation effort required to find the real nest. Since the higher the cost expended to find food indicates more energy is exerted, predators may be dissuaded from searching for the eggs. Increased search and excavation costs have been shown to alter nest predator foraging behaviour and predation risk, especially in nest raiders which primarily detect nests from tactile, visual, and chemosensory cues.

As seen from this study, this behaviour has been shown in leatherback and hawksbill turtles but is likely to apply to all seven species of marine turtle, showing that female turtles invest more energy into protecting their eggs than previously thought.

References:

Burns, T.J., Thomson, R.R., McLaren, R.A., Rawlinson, J., McMillan, E., Davidson, H., Kennedy, M.W., (2020). ‘Buried treasure—marine turtles do not ‘disguise’ or ‘camouflage’ their nests but avoid them and create a decoy trail’, The Royal Society , 7(5). doi: 10.1098/rsos.200327

Emirates Global Aluminium (2019) Hawksbill turtles begin to arrive at Abu Dhabi nesting site. Available at: https://www.thenational.ae/uae/environment/hawksbill-turtles-begin-to-arrive-at-abu-dhabi-nesting-si... (Accessed: 4 June 2020)

Leighton, P.A., Horrocks, J.A. and Kramer, D.L., 2011. Predicting nest survival in sea turtles: when and where are eggs most vulnerable to predation?. Animal Conservation , 14 (2), pp.186-195

National Park Service (2017) Sea Turtles . Available at:

https://www.nps.gov/caha/learn/nature/seaturtles.htm (Accessed: 4 June 2020)

State of the World’s Sea Turtles. Leatherback. Available at: https://www.seaturtlestatus.org/leatherback-turtle (Accessed: 4 June 2020)

SHARE THIS ARTICLE