Venomous What? The Significance of Knowledge Gaps Concerning Venomous Chondrichthyans.

When cartilaginous fish (chondrichthyans) are brought up in conversation or by the media, sharks are usually the go-to focus, often overshadowing their weird and wonderful relatives. Afterall, they are the big bad poster boys of the sea. Despite this arguably misplaced stigma, it is probably fair to say that in most people will initially think of shark teeth and the damage they can cause, as opposed to how important sharks or their relatives are, their conservation, and other less nefarious aspects of their potential clinical significance.

Now those who have had the pleasure of coming close enough to touch one of these abyssal ambassadors can vouch for the fact they technically have more sharp, toothy bits outside of their mouth than inside. These rough and sharp external defences usually take the form of placoid scales, otherwise known as dermal denticles due to similarities to teeth, such as a vascular inner core, a central layer of dentine, and being coated in a hardened enamel-like layer of vitrodentine. However, many cartilaginous fish also possess sharp spines and barbs capable of causing notable harm, including haemorrhaging.

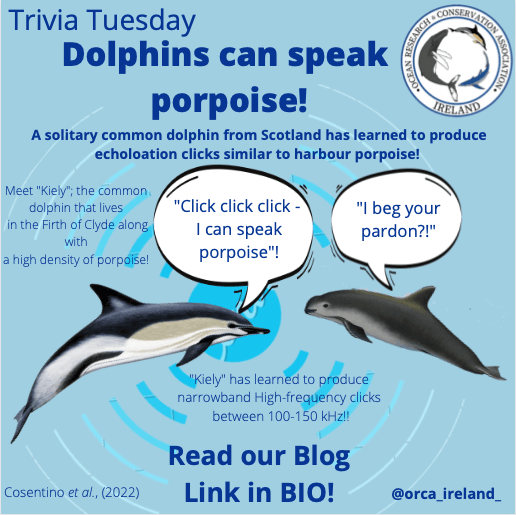

If the thought of specialised teeth, abrasive skin, and penetrating spines wasn’t dangerous enough for some of you, highlighting the fact that species such as the horn shark ( Heterodontus francisci - figure 1) possess venom glands would be enough to push some people over the edge. Selacho- and Thalassophobics are no doubt already screaming about whether such animals really needed another way to harm people, but rest assured fish venom is primarily defensive. This is supported by the venom delivery apparatus being some form of spine as opposed to a tooth and the primary symptom of chondrichthyan envenomation being immediate pain, not just arising from the wound itself (Halstead and Vinci, 1987., Smith et al., 2014). So, unless they plan on hugging or working with these animals, the regular bitey-end should be enough for people to worry about. Besides, these animals receive far worse press than they warrant. Whilst some species are circumstantially dangerous, they are all ecologically significant spectacles to behold.

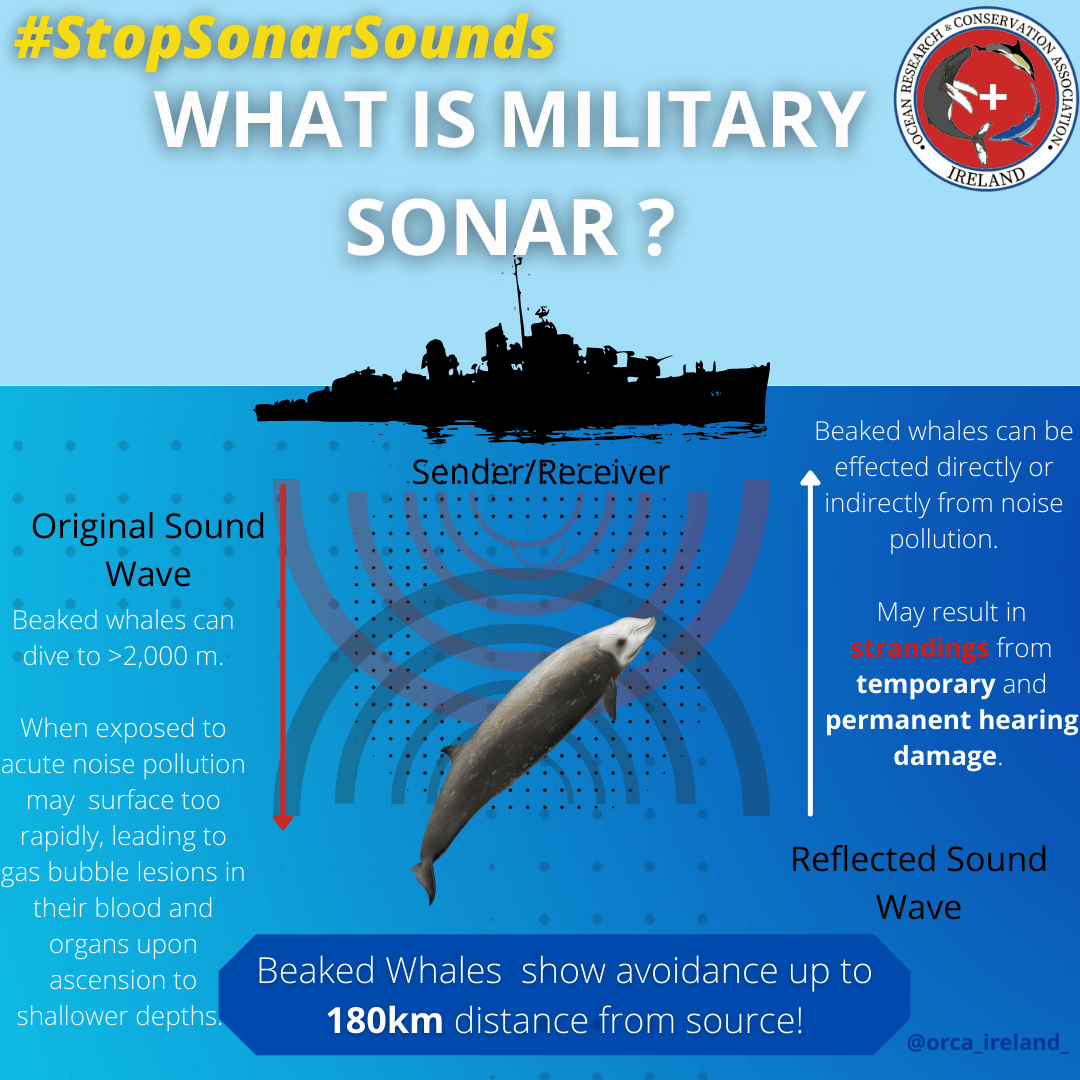

Venom is not usually a concern on an island lacking snakes, but venomous chondrichthyans can be found around the globe, including the Atlantic waters surrounding Ireland (i.e. the common stingray, Dasyatis pastinaca, and ratfish, Chimaera montrosa - figure 2). Stingrays alone constitute one of the most clinically significant sources of envenomation from any one taxonomic group of marine and freshwater fish, with as many as 2000 cases being recorded in the USA alone within a single year (Scharf, 2002). Cazorla (2009) showed that longnose stingray ( Dasyatis guttata ) envenomations are often characterised by symptoms such as intense, rapid localised, radiating and even spasmodic pain, shortness of breath (dyspnea), changes in blood pressure, and elevated heart rate (tachycardia).

Other symptoms associated with stingray venoms include vomiting, diarrhoea, sweating, and muscular paralysis as noted by Halstead (1987), who also identifies some of the clinical symptoms for Chimaera envenomation. Similarly, these include an intense, escalating pain which can persist for several hours and remain as a dull ache for several days, as well as the deoxygenation of the blood and associated blue discolouration of the skin or mucous membranes (cyanosis), swelling of the site and lymph nodes, and joint pain. Knowledge of clinically significant encounters with chondrichthyans should subsequently be more important. Not just because of the potential for significant harm during recreation, but because cartilaginous fish are regularly encountered as bycatch, making this issue an occupational hazard. This includes holocephalans such as C. monstrosa , known to have caused clinically significant injuries to fishermen within the northeastern Atlantic waters surrounding the British Isles and Europe (MagerØy and Baerheim, 1991., Hayes and Sim, 2011).Despite the clinical significance of these species, the mechanisms and composition of venoms associated with chondrichthyans and many other marine organisms is yet to be properly studied, especially when compared to toxic terrestrial taxa such as snakes (Casewell et al. , 2013). This can be considered quite the oversight, as lack of accurate information concerning species specific envenomation and its treatment can result in excess pain, morbidity and mortality within any toxic taxa. This can be due to differences in venom composition and pathologies (symptoms, causes and effects) within and between species, populations and even individuals (venom variation).

One factor responsible for these knowledge gaps and the disparity in research is the sensitivity of fish venoms to a variety of parameters, inhibiting preservation and storage. Further issues arise due to the mucus associated with the venom delivery system contaminating venom samples, interfering with the study of biologically active proteins in the venom (proteomics). The few pathological and venomic studies that have taken place are usually restricted to stingrays. Bauman (2014) conducted the first combined investigation into the gene and protein composition present within the venom apparatus of any known fish, the blue spotted stingray (Neotrygon kuhlii - figure 3), creating a novel protein handling method in the process and enabling future studies. Bauman et al. (2014) showed the venom of N. kuhlii is highly complex and contains novel toxins not identified within other animal venom systems (i.e. cystatin, peroxiredoxin, galectin).

The clinical significance of cartilaginous fish and discovery of novel toxins within chondrichthyan venom further highlights why marine venoms should be of significant interest to both the scientific community and general public. Not just because of the direct impacts it can have on those unfortunate enough to be on the receiving end of a sting or bite, but because of the novel therapeutics that can be derived from them. Afterall, nobody wants to suffer through the effects of the toxins or treat cases blind, and most people also won’t turn down efficient medications and treatments generated from the very same toxins.

So why should marine venoms continue to be neglected? Therapeutic development has frequently been achieved with terrestrial, predominantly haemotoxic reptile venoms such as that of the saw scaled viper, Echis carinatus (Echistatin - Gan et al. , 1988). Sadly, as suggested, marine derived therapeutics are somewhat trailing behind despite the few rare exceptions being highly successful and warranting further study. One such example is Ziconotide, a potent, non-addictive painkiller more powerful than morphine, which was approved between 2004 and 2005 worldwide, in spite of originating from cone snail ( Conus magus ) toxins first identified in 1982 (McIntosh et al. , 1982., Safavi-Hemami et al. , 2019). Hopefully it won’t take the next 20 years for venomous sharks, rays and ratfish to receive some much-needed love. Perhaps Ireland can help lead the way thanks to the acclaimed venom laboratory based at the National University of Ireland Galway.

References:

Bauman, K., Casewell, N.R., Ali, S.A., Jackson, T.N.W., Vetter, I., Dobson, J.S., Cutmore, S.C., Nouwens, A., Lavergne, V., and Fry, B.G. (2014). A ray of venom: Combined proteomic and transcriptomic investigation of fish venom composition using barb tissue from the blue-spotted stingray ( Neotrygon kuhlii ). Journal of Proteomics. 109: 188 – 198.

Cazorla, D., Loyo, J., Lugo, L., and Acosta, M. (2009). Clinical, epidemiological and treatment aspects of 10 cases of saltwater stingray envenomation. Revista de Investigaci ón Cl ínica. 61 (1): 11 – 17.

Casewell, N.R., Wüster, W., Vonk, F.J.,Harrison, R.A., and Fry B.G. (2013). Complex cocktails: The evolutionary novelty of venoms. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 28: 219 – 29.

Gan, Z.R., Gould, R.J., Jacobs, J.W., Friedman, P.A., and Polokoff, M.A. (1988). A potent platelet aggregation inhibitor from the venom of the viper, Echis carinatus . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (36): 19827 – 19832.

Halstead, B.W., and Vinci, J.M. (1987). Venomous Fish Stings (Ichthyoacanthotoxicoses). Clinics in Dermatology. 5 (3): 29 – 35.

Hayes, A.J., and Sim, A.J.W. (2011). Ratfish (Chimaera) spine injuries in fishermen. Scottish Medical Journal. 56 (3): 161 – 163.

MagerØy, N., and Baerheim, A. (1991). Ratfish ( Chimaera monstrosa ) sting. Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening: Tidsskrift for Praktisk Medicin, ny Raekke. 111 (17): 2102 – 2103.

McIntosh, M., Cruz, L.J., Hunkapiller, M.W., Gray, W.R., and Olivera, B.M. (1982). Isolation and structure of a peptide toxin from marine snail Conus magus . Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 218 (1): 329 – 334.

Safavi-Hemami, H., Brogan, S.E., and Olivera, B.M. (2019). Pain therapeutics from cone snail venoms: From Ziconotide to novel none-opioid pathways. Journal of Proteomics. 190: 12 – 20.

Scharf, M.J. (2002). Cutaneous injuries and envenomations from fish, sharks and rays. Dermatologic Therapy. 15: 47 – 57.

Smith, W.L., Stern, J.H., Girard, M.W., and Davis, M.P. (2014). Evolution of Venomous Cartilaginous and Ray-Finned Fishes. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (5): 950 – 961.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE