Where Do Sea-turtles Lay their Eggs?

Sea turtles respond to environmental cues and variability when assessing site suitability for their egg chamber on sandy beaches. Nest site selection is the last form of parental investment for these animals. As a result, they try to select somewhere which will increase the hatchling’s chance of survival and overall fitness. An understanding of how this behaviour evolves is paramount for conservation measures to be effective in protecting sea turtles.

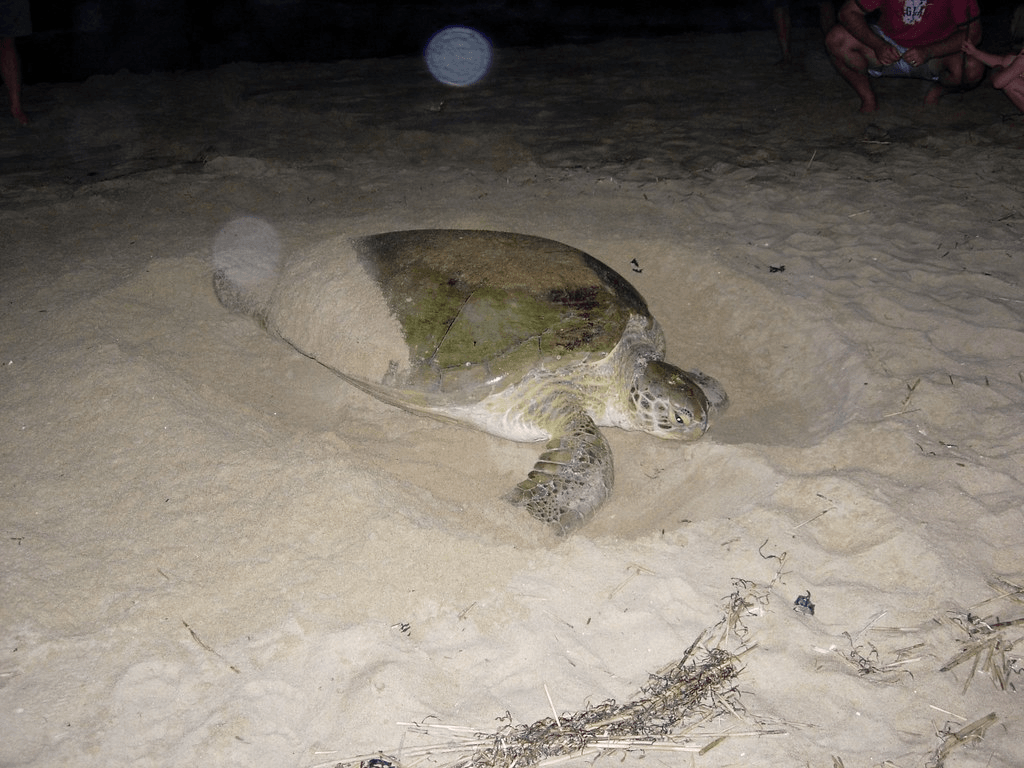

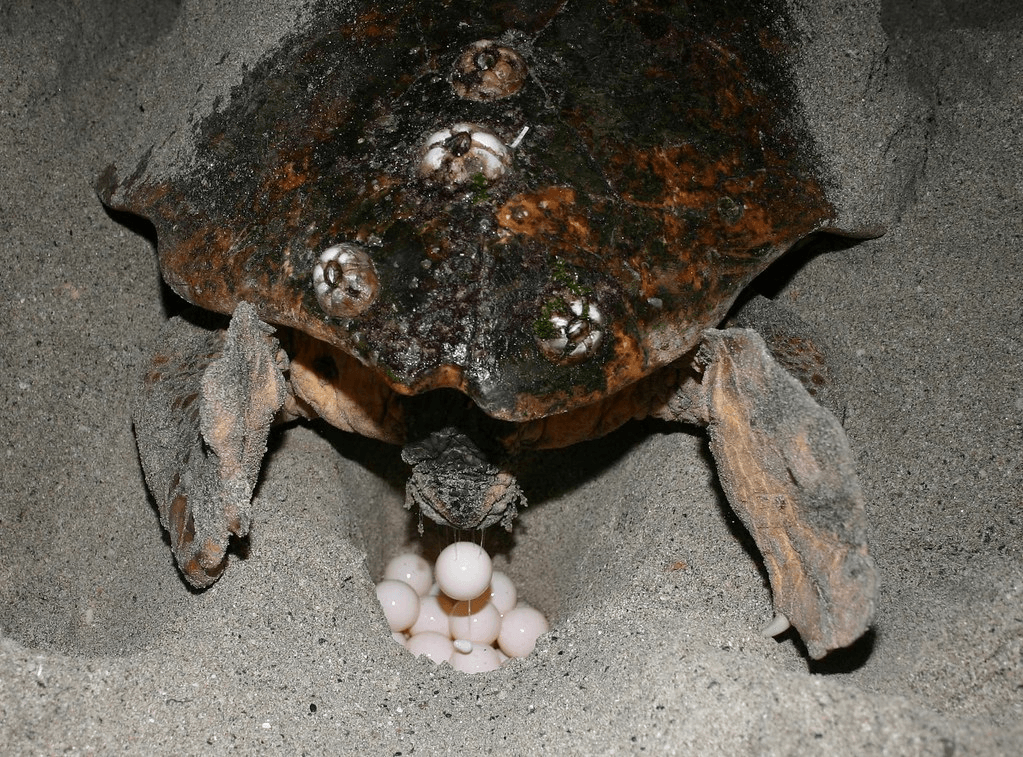

Although sea turtles spend most of their life at sea, females crawl onto sandy beaches to dig egg chambers to lay their eggs. Multiple clutches are laid within a breeding season which occurs every 2-4 years. Females select particular locations to lay their nest to provide their offspring with the best chance of survival. Nest site selection is critical in sea turtles as after this, no further form of parental care occurs. What factors are important when choosing the perfect site? Is this behaviour genetically inherent or is it learned? How will they be impacted by climate change?

Sea turtles display fidelity to their natal site. This is known as philopatry, and is when a female turtle returns to the beach from which it hatched to lay its own nest. However, this cannot be the only driving force of site selection as environmental conditions may not always permit females to returnto their natal site. For instance, loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta have been shown to return to their general natal region but perhaps on a different beach. They can respond to changing beach profiles and environmental conditions by relocating to a different beach. This suggests that nest site selection is not entirely inherent. In fact, experienced nesting females choose more successful nest sites in contrast with first time breeders. It is therefore thought that females are using information about microhabitat conditions, beach morphology and sediment to select the most suitable nest site. The ability to relocate from their natal site if it was not suitable suggests that there is potential for them to adapt to the environmental changes accelerated by global warming.

Nests that are laid on low beach levels are more susceptible to flooding. Meanwhile, hatchlings coming from the back of the beach are more vulnerable to predation, entanglement from vegetation and misorientation as they crawl to sea. A study on green sea turtles Chelonia mydas in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa found that different microhabitats drive the development of divergent advantageous traits in the hatchlings. Large females can venture to higher elevations due to their enhanced locomotor ability and lay nests which will produce large-sized hatchlings. Increased body size elevates their chance of survival as they crawl to sea, where they are vulnerable to predators. In contrast, hatchlings born closer to the water are less susceptible to such threats and do not need to expend energy on increased body size. Instead they can conserve energy reserves for their journey at sea, while learning to forage food for themselves. Nesting females therefore exhibit different preferences of site location but hatchling survival is at the forefront of these decisions.

Sea turtles exhibit an interesting phenomenon called temperature dependent sex determination. This means that chamber temperature during incubation influences the sex of the offspring. In sea turtles, high temperatures drive the development of females. Nests at higher elevations near vegetation are predominantly cooler than those near the sea line. As a result, nests at lower elevations are likely to have unbalanced sex ratios with predominantly females. This negatively impacts reproduction rates and the stability of the population.

How deep into the sand does the female dig to make the egg chamber? Variations in depth influence the sex and fitness of hatchlings due to changes in temperature. A study carried out on loggerheads in Boa Vista Island, Republic of Cabo Verde found that cooler nests buried deeper in the sand , had greater emergence success and offspring with enhanced locomotor abilities. Not only that, these nests at 50cm below ground produced more balanced sex ratios in comparison with ones at warmer shallower depths (35cm) where females dominated the clutch. Will females adapt to digging deeper chambers in response to climate change increasing surface temperatures?

Egg relocation is a widely used conservation measure on sea turtle nests. This involves removing a nest from a dangerous area to a safer location. However, there are concerns that this could cause artificial selection on turtles nesting in unsuccessful sites. According to Pfaller et al . (2009), for this to occur, nest site selection must be a heritable trait and high individual repeatability in choosing a particular site must occur. For instance, hawksbill sea turtles Eretmochelys imbricata in the French West Indies consistently nest in the same site between and within breeding seasons. As a result, egg relocation would cause artificial selection in this population. In contrast, populations of loggerheads in Cephalonia, Greece do not show this same level of repeatability. Loggerheads in Cephalonia must assess site suitability, as environmental factors fluctuate more often here than in the French West Indies. Egg relocation would be an appropriate conservation measure for Cephalonia loggerheads. This method should be considered along with knowledge of individual sea turtle population nesting patterns and beach stability across years.

Environmental factors can be intercepted by artificial light on beach fronts. Loggerheads on St George Island in Florida, USA nest less frequently in zones with increased artificial light than in dark areas. Female nesting turtles are being discouraged to return to their natal site due to the growing levels of building developments that produce light pollution. It is therefore paramount that studies on nesting species continue to enable local government agencies to develop informed strategies that consider the conservation of these animals.

References:

Marco, A., Abella, E., Martins, S., López, O. and Patino-Martinez, J. (2018). Female nesting behaviour affects hatchling survival and sex ratio in the loggerhead sea turtle: implications for conservation programmes. Ethology Ecology & Evolution , 30(2) , pp.141-155.

Patrício, A.R., Varela, M.R., Barbosa, C., Broderick, A.C., Airaud, M.B.F., Godley, B.J., Regalla, A., Tilley, D. and Catry, P. (2018). Nest site selection repeatability of green turtles, Chelonia mydas , and consequences for offspring. Animal Behaviour , 139 , pp.91-102.

Pfaller, J.B., Limpus, C.J. and Bjorndal, K.A. (2009). Nest‐site selection in individual loggerhead turtles and consequences for doomed‐egg relocation. Conservation Biology , 23(1) , pp.72-80.

Price, J.T., Drye, B.R.U.C.E., Domangue, R.J. and Paladino, F.V. (2018). Exploring the role of artificial lighting in loggerhead turtle ( Caretta caretta ) nest-site selection and hatchling disorientation. Herpetological Conservation and Biology , 13(2) , pp.415-422.

Santos, A.J.B., Neto, J.X.L., Vieira, D.H.G., Neto, L.D., Bellini, C., De Souza Albuquerque, N., Corso, G. and Soares, B.L. (2016). Individual nest site selection in Hawksbill turtles within and between nesting seasons. Chelonian Conservation and Biology , 15(1) , pp.109-114.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE